This is Part Two in the fourth of twenty-five weekly articles in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Series. Students in grades 8 through 12 can sign up here to participate in The Tennessee Star’s Constitution Bee, which will be held on September 23.

(You can read Part One of How and Why Thirteen States Ratified the Constitution: 1787 – 1790 here.)

On January 9, the same day Connecticut officially said yes, 370 delegates to the Massachusetts ratifying convention convened at the Massachusetts State House in Boston.

“The Old State House, the oldest surviving public building in Boston, was built in 1713 to house the government offices of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. It stands on the site of Boston’s first Town House of 1657-8, which was destroyed by fire in 1711. As the center of civic, political, and business life, the Old State House was a natural meeting place for the exchange of economic and local news. A merchant’s exchange occupied the first floor, and John Hancock and others rented warehouse space in the basement. The National Historic Sites Commission has called the Old State House one of the most important public buildings in Colonial America. . . The central area of the second floor was the meeting place of the Massachusetts Assembly, the most independent of the colonial legislatures, and the first to call for sectional unity and the formation of a Stamp Act Congress,” the Bostonian Society website says. (click to see the whole picture)

Everyone knew that the outcome in Massachusetts, the second most populous of the thirteen states, was critical, and that the issue was very much in doubt, as Federalists and Anti-Federalists jockeyed for position in the lead up to the convention.

“When Paul Revere learned that Sam Adams and John Hancock were reluctant to offer their support for the Constitution during the ratification fight, he organized the Boston mechanics into a powerful force and worked behind the scenes for the successful approval by the Massachusetts convention,” Constitution Facts notes.

Proceedings began on a sour note, an indication of the contentious discussions yet to come, when the delegates began to complain about their meeting location, which was designed to house the state’s much smaller legislative bodies.

“The delegates complained that the State House facilities were overcrowded. On January 17, the convention moved to the Long Lane Congregational Church,” Teaching American History notes.

The Long Lane Meeting House was torn down long ago, but the congregation, now part of the Unitarian Church, continues to exist under another name at a different location in Boston. (click to see the whole picture)

Prominent Boston merchant John Hancock, famous for his outsized signature on the Declaration of Independence, was a delegate to the ratifying convention who had originally leaned in favor of the Anti-Federalist position. He proposed “The Massachusetts Comprise” –ratify now, amend with a Bill of Rights later– and Samuel Adams, the famous firebrand who helped start the Revolution, another Anti-Federalist, supported the comprise.

On February 6, 1788, the ratifying convention voted.

“What is clear is that the Massachusetts Compromise secured the victory for the proponents of the Constitution because roughly ten delegates changed their mind to secure ratification by a 187-168 vote,” Professor Gordon Lloyd wrote.

Prominent Boston merchant John Hancock, famous for his outsized signature on the Declaration of Independence, proposed “The Massachusetts Comprise” –ratify now, amend later . (click to see the whole picture)

On February 6, 1788, the ratifying convention voted.

“What is clear is that the Massachusetts Compromise secured the victory for the proponents of the Constitution because roughly ten delegates changed their mind to secure ratification by a 187-168 vote,” Lloyd wrote.

Samuel Adams supported the Massachusetts Compromise. (click to see the whole picture)

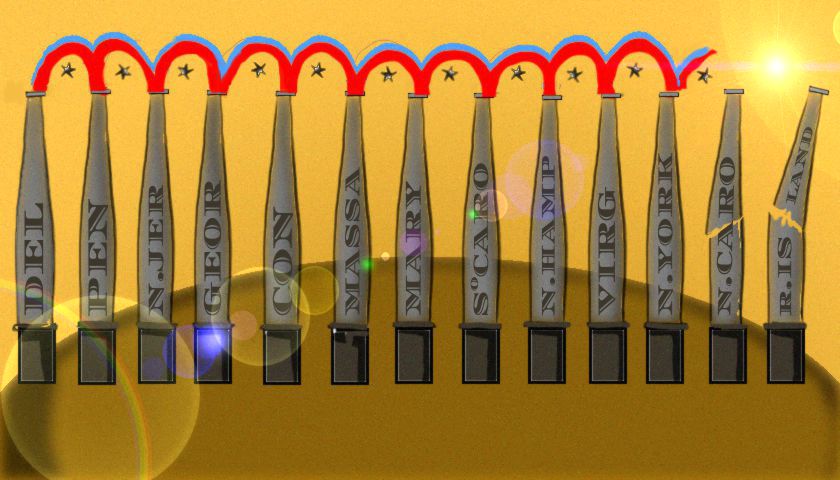

The Massachusetts Centinel, a Federalist newspaper “published in Boston on Wednesdays and Saturdays by Benjamin Russell (1761–1845) . . . specialized in the brief article that, in vigorous and colorful language, extolled the Constitution or scored its critics,” according to the Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution.

“Russell was an early advocate of increasing the powers of the central government. While the Constitutional Convention sat, the Centinel was filled with articles that advocated strengthening Congress,” the Documentary History notes:

He attended the Massachusetts convention and took notes of the debates, which were published in the Centinel. No other printer celebrated the

ratification of the Constitution more originally than Russell. On 16 January 1788, a week after Connecticut had ratified, Russell

printed an illustration of five pillars, each representing a state that had ratified the Constitution. Each time a state ratified, he added

another pillar. Russell’s originality and partisanship made the Centinel one of the most often reprinted newspapers in America. (emphasis added)

The Centinel’s publisher, Benjamin Russell, showed the hand of God pushing the Massachusetts pillar to an upright position in this illustration for his paper published just a few weeks before the Massachusetts ratifying convention convened in Boston. (click to see the whole picture)

Up next was New Hampshire, where, as Professor Lloyd noted, “many a campaign has fallen on hard times . . . in February.”

The New Hampshire convention met on February 13. To the surprise of the pro-Constitution forces, it was discovered that a majority of the delegates were actually opposed to ratification! Of the 108 delegates in attendance, fewer than 50 were in favor of adoption. According to Jackson Turner Main, “only thirty favored ratification.”

And the going was so tough that the Madisonian forces proposed a strategy that they implemented on February 22. The strategy in New Hampshire was to adjourn in order to avoid what was beginning to look like the first ratification defeat. So they postponed with the intention of coming back later. That’s the low-ground explanation for the delay. The high-ground explanation was that the delay allowed the delegates who were elected, perhaps even instructed by their constituents to oppose ratification, before they knew that five states would ratify before New Hampshire’s convention even met, to go back to their district and make sure that their constituency still felt the same way about rejecting the Constitution.

With New Hampshire “on hold,” all eyes turned southward.

“Given the concerns expressed by the delegates from Maryland and South Carolina at the Philadelphia Convention, one might anticipate that there would be quite a confrontation in Maryland and South Carolina,” Lloyd wrote:

But the delegates from these two states adopted the Constitution very easily: 63 to 11 [in Maryland on April 26, 1788] , and 149 to 73 [in South Carolina on May 23, 1788], respectively. More importantly, these “exit votes” were virtually the same as the “entrance votes” going in to the ratifying conventions. Moreover, there wasn’t much of a debate despite the official declarations that the proposed Constitution had been “fully considered.” The problem is that we will never know why Maryland and South Carolina didn’t put up much of an opposition. The official records are very sparse. We can only speculate as to why the Antifederalists failed to mount a credible challenge at this stage of ratification. Jackson Turner Main puts it down to a biased press and the location of the state ratifying conventions.

The Centinel published this version of the Federal Pillars as one state remained to reach the magic number of nine that would form a new republic under the Constitution. (click to see the whole picture)

“The fate of the Constitution virtually hung in the balance during the summer of 1788. While it was true that Madison only needed the affirmative vote of one of those three state ratifying conventions and the Antifederalists needed all three, if you look at the predicted vote going in, then it was clear that Madison had some very real problems. New Hampshire was 52-52, Virginia was 84-84, and New York was 19 in favor and 46 against by what today we might call ‘entrance polls.’ It was going to be an extremely close call,” Lloyd explained:

In preparation for the June New Hampshire ratifying convention, the Federalist leaders were far more active in their campaigning than in February. Even then, it turned out that the vote was virtually even going into the convention. It turns out, furthermore, that five delegates adopted the Massachusetts Compromise in New Hampshire after three days of debate. Thus the Constitution was officially ratified on June 21, 1788 by a vote of 57-47. According to Jere Daniell, only calculated and manipulative political maneuvering by Sullivan and Langdon carried the day.

Immediately after the news of the new nation spread throughout the state, the first of the public celebrations–which would be referred to as “Federal Processions” took place in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.

The New Hampshire ratifying convention met in the Old North Meeting House in Concord, New Hampshire. (click to see the whole picture)

Now, there was a new country consisting of nine states, but it was divided into three disconnected geographic regions: New England, which was separated from the Mid-Atlantic states by New York, which were in turn separated from the Southern states by Virginia.

For the entire enterprise to work, both Virginia and New York needed to ratify the Constitution, but that remained very much in doubt.

“Governor Edmund Randolph presented the proposed Constitution to the Virginia Assembly in mid-October 1787 and the legislative branch provided for the election of delegates to a state ratifying convention,” Lloyd wrote:

“Two delegates were selected from each of the 84 counties,” and the ratification convention began on June 2, 1788:

Among those delegates who defended the Constitution at the Virginia Ratifying Convention were James Madison, “father of the Constitution;” John Marshall, future Chief Justice of the Supreme Court; and Governor Randolph who nearly a year earlier introduced the Virginia Plan and was one of two Virginia delegates to the Constitutional Convention who refused to sign on September 17, 1787. Opposing adoption of the Constitution were such heavyweights as George Mason, author of the Virginia Bill of Rights and the other non-signer in Philadelphia; Patrick Henry, renowned for his inflammatory, dominating, and passionate speeches; William Grayson, delegate to the Confederation Congress, and James Monroe, future President of the United States and author of the Monroe Doctrine.

Three weeks later, on June 25, “The delegates then voted 89-79 to ratify the Constitution with a recommendation that “subsequent amendments” be sent to the First Congress for their consideration,” an outcome made possible only because several delegates who arrived as Anti-Federalists changed their minds during the debates.

Now the Mid-Atlantic states were connected to the South, but New England remained separated by New York, which, “in many ways, was at the center of the ratification controversy,” according to Lloyd.

On June 16, 1788 the New York ratification convention convened in Poughkeepsie, 90 miles north of New York City. Alexander Hamilton was the most prominent Federalist delegate in attendance:

Starting June 17, the delegates proceeded to go paragraph by paragraph through the Constitution during the first week of the Convention. Early in the second week — June 24 — the delegates received news that New Hampshire, the critical ninth state, had ratified. But the debate continued. Then news that Virginia had ratified reached New York at the end of June. Although the delegates continued their discussion through July 7, there were various moves taking place to seek a compromise solution. Between July 7 and July 14, Antifederalist attempts to secure conditional amendments as well as secession guarantees were defeated. On July 26, New York, by a vote of 30-27 — on the promise of recommended amendments— ratified the Constitution and proposed 25 items in a bill of rights and 31 amendments.

After New York and Virginia ratified the Constitution, bringing the total number of states participating in the new republic to eleven, the Centinel published this image of the Federal Pillars, indicating the danger for North Carolina and Rhode Island if they failed to become the twelfth and thirteenth states to ratify. (click to see the whole picture)

The Massachusetts Centinel celebrated by publishing an updated version of its now famous “Federal Pillars” drawing, which showed eleven strong upright pillars, and only two–North Carolina and Rhode Island–falling towards the ground.

In New York City, the grandest of all “Federal Processions” was held in August, featuring a horse drawn vessel bearing the name “Hamilton.”

Alexander Hamilton was the hero of the day during the Federal Procession in New York City celebrating the state’s ratification of the new Constitution. (click to see the whole picture)

The North Carolina ratification convention was finally under way. News of New York’s ratification reached them just before they adjourned, but lacking a clear commitment to a Bill of Rights, the vote for ratification failed.

“Meeting in Hillsborough, North Carolina, delegates convened from July 21 to August 4, 1788 to consider ratification of the newly proposed federal Constitution. Key state Federalists were James Iredell Sr., William Davie, and William Blount. Antifederalist leaders included Willie Jones, Samuel Spencer, and Timothy Bloodworth. Governor Samuel Johnston presided over the Convention. The two-week long deliberations resulted in neither ratification nor rejection. The 1789 Fayetteville Convention continued the debate,” North Carolina History.org reports.

Another key Federalist delegate in attendance was Dr. Hugh Williamson, for whom Williamson County in Tennessee was named.

“Congressional and Presidential elections took place in November 1788, and the First Congress met in March 1789,”Lloyd wrote.

James Madison, one of the two most well known Federalists in the country, won a hard fought campaign to represent his Virginia Congressional District against his Anti-Federalist opponent, James Monroe, largely on the basis of his promise to introduce and support a Bill of Rights when the first Congress convened.

When the first Congress convened in New York City in March, 1789, Madison was true to his word.

“Learning that Congress endorsed a version of Madison‘s Bill of Rights proposal, North Carolina held a second ratifying convention. This time, on November 21, 1789, the delegates ratified the Constitution,” Lloyd wrote.

“And then there is Rhode Island. Between February 1788 and January 1790, the Assembly refused 11 times to call a ratifying convention. At the end of the second session of the First Congress, the Senate sent Rhode Island a message which, in effect, said: “Join or die.” Rhode Island finally held a convention, having rejected earlier attempts to hold a ratifying convention, and they joined the Union. The delegates ratified the Constitution by a vote of 34 to 32 on May 29, 1790. They also had the nerve to propose that the First Congress recommend the adoption of a bill of rights as well as amendments to the Philadelphia Constitution,” Lloyd noted.

“Rhode Islanders finally acted after several neighboring states threatened to tax its exports as though it were a foreign country. All in all, 11 attempts to hold constitutional ratifying conventions failed, along with several unsuccessful referenda. Residents of the former British colony rejected the first effort to approve the Constitution by a margin of 10-to-1,” Andrew Glass writes.

Rural areas voiced particularly strong opposition to the Constitution; from 1786 to 1790, an anti-federalist “Country Party” controlled the General Assembly. In 1788, William West, an anti-federalist politician and Revolutionary War general from Scituate, led an armed force of 1,000 men to Providence, the colonial capital, with the aim of breaking up a Fourth of July celebration marking New Hampshire’s breakthrough ratification vote.

Rhode Island convention finally ratified the Constitution “on May 29, 1790 (over a year after President George Washington’s inauguration) by a vote of 34-32,” Constitution Facts notes.

Three full years after the delegates gathered at the Constitutional Convention, all thirteen states were now joined in the new republic.

But there was still more than a year of work ahead before the entire covenant that bound the new country together was completely sealed.

[…] in February 1788, the Constitution was ratified by the sixth state-Massachusetts-only after the Massachusetts Compromise proposed by John Hancock and supported by Samuel Adams–was accepted by the ratifying […]

[…] You can read How and Why Thirteen States Ratified the Constitution: 1787 – 1790 (Part Two) here. […]